Delves into Canada’s civil rights evolution over the centuries and dispels misconceptions about Canada’s civil rights record

Conrad Black’s latest book, Forgotten History: Civil Rights in Canada, is an insightful work that dispels many cheap slanders and misconceptions about Canada’s past. Black combines a deep knowledge of Western history and an eye for relevant historical details to help shine a new light on Canada’s civil rights record.

Conrad Black’s latest book, Forgotten History: Civil Rights in Canada, is an insightful work that dispels many cheap slanders and misconceptions about Canada’s past. Black combines a deep knowledge of Western history and an eye for relevant historical details to help shine a new light on Canada’s civil rights record.

Interest in this book may be heightened by the recent calls to upend historically won civil rights in Canada in the name of social justice. Or it might also come from the rise in new identity-based subgroups – whose demands for collective rights often infringe upon the rights of the individual. Finally, it may even come from Quebec’s recent string of rights violations being imposed on the English-speaking population within that province.

Given these emerging trends, Black’s look into the origins and development of Canada’s civil rights provides an essential historical perspective that can help to ground these discourses. Black’s work tracks the origins and development of civil rights in Canada over hundreds of years, which, he argues, culminated in the confirmation of these rights in the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms.

There has been a growing tendency in academic circles to paint all of Canada’s history with one broad brush, and this lack of nuance has contributed to a collective forgetting of Canada’s past. As such, Black’s book serves as a welcomed reminder of this past and helps deepen our understanding of rights-based politics in Canada.

His book explores the origins and manifestation of Canada’s English and French approaches to political rights, the history and abolishment of slavery in Canada, Indigenous rights and history, the movement for democratic rights and citizenship, and the Canadian Charter, among others.

The foundations of Canada

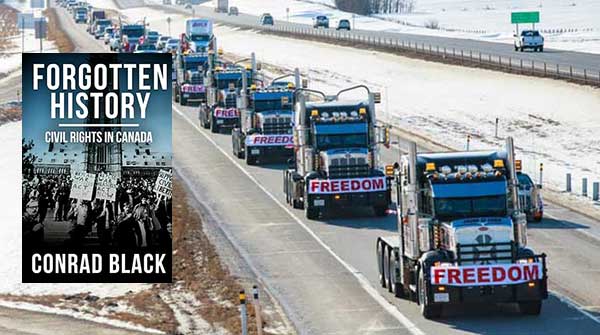

Photo by Naomi Mckinney |

| Related Stories |

| Canada has a robust history of freedom

|

| The next election will be a common sense revolution

|

| Trudeau turned to the dark side in response to Covid-19

|

Forgotten History starts with an exploration of the early forces that moulded civil rights in Canada. This journey encompasses pre-colonial Aboriginal societies, the influence of 18th-century European powers, and the intricate political tensions that unfolded among the British, French, and American colonies during the Seven Years’ War and the American Revolution.

Forgotten History starts with an exploration of the early forces that moulded civil rights in Canada. This journey encompasses pre-colonial Aboriginal societies, the influence of 18th-century European powers, and the intricate political tensions that unfolded among the British, French, and American colonies during the Seven Years’ War and the American Revolution.

By examining these early conflicts, Black vividly illustrates how Canada’s distinct system of rights, fusing elements of both French and English origins, became an integral part of its very foundation. This transformative process took root in 1763 when Quebec transitioned from French to British control at the culmination of the Seven Years’ War.

During this pivotal juncture, Britain’s acquisition of Quebec coincided with the American colonies’ rebellion against alleged British over-taxation. These circumstances led to British apprehensions that Quebec might align itself with the rebellion, potentially jeopardizing Britain’s interests in North America.

Black underscores that, despite the legitimacy of Britain’s concerns, the majority of Quebecers opposed the American style of governance. They feared that its strong emphasis on individual rights would ultimately lead to their assimilation into the English-speaking majority.

Nonetheless, a mutual interest emerged between the British and the Quebecois, culminating in the implementation of the Quebec Act of 1774. This significant Act afforded Quebec certain provisions safeguarding the French language and the Roman Catholic faith. Additionally, it reintroduced French Civil Law alongside British Criminal Law.

However, a significant drawback for Quebec was the establishment of an all-British legislative council responsible for governing the province. This absence of representation stemmed from pre-existing British laws that barred French Roman Catholics from participating in the administration of affairs throughout the British Empire.

Black observes that, despite the absence of democratic or self-governing rights, Quebec viewed these terms as a reasonable concession for several compelling reasons:

- Quebec had a limited appetite for democracy, primarily due to the historical suppression of democratic ideals by France’s Chief Minister Cardinal Richelieu a century earlier.

- The new British governors exhibited a considerably higher degree of political integrity than their corrupt French predecessors in Quebec.

- The French criminal law system had not yet adopted Habeas Corpus, leading to a presumption of guilt for the accused. Furthermore, the practice of torturing suspected criminals to extract confessions remained commonplace in French criminal law. Consequently, French Canadians retained their civil law tradition while transitioning to British criminal law.

Black contends that this unique political climate played a pivotal role in establishing Canada’s foundations of rights, harmoniously blending elements from both English and French influences.

The citizenship rights of Canadian immigrants

Today, we extend citizenship rights to newly arrived immigrants, a privilege often denied to newcomers in many other countries around the world. Black’s book delves into the historical development of citizenship rights in Canada. This process began following the American Revolution when numerous British Loyalists migrated from the United States to Canada. During this period, no formal procedure was established for naturalizing these Loyalists as Canadian citizens. Consequently, when the War of 1812 erupted with the United States, there was significant pressure to expel, surveil, and disqualify them from holding public offices or positions.

This issue reached a critical juncture in the 1820s when it was politically exploited to disqualify an American settler from assuming a position in the Assembly. Ultimately, in 1828, a bill was enacted to naturalize all individuals who had arrived in Upper Canada before 1821. This legislative action created a rational naturalization process for future immigrants, setting a foundational precedent in Canada that would benefit millions of newcomers seeking refuge or opportunities in the country.

The attainment of democratic rights in Canada

Another pivotal moment in the evolution of rights in Canada involved the acquisition of democratic rights, a process carefully navigated through intricate political negotiations between Canada and the British government.

Black underscores that, following the War of 1812, a sense of national identity began to take root in Canada, accompanied by a growing desire for democratic representation. However, during this period, Canada’s governing authority still rested with Britain, necessitating cautious diplomacy in its appeals to the British government. While Canada could advocate for responsible government, it had to be mindful not to strain the relationship to the point where Britain might lose patience and consider selling the colony to the United States for financial gain or territorial concessions.

Similarly, Black observes that a full-scale rebellion against Britain was hardly feasible for Canada, as it had been for the original 13 American colonies. Britain possessed the military might to suppress any uprising in Canada, and Canada relied entirely on the British military to deter potential American invasions – a cause championed by numerous American politicians throughout the 19th century. Consequently, early Canada was compelled to pursue a patient and cautious path toward asserting its democratic rights.

These efforts culminated in the 1837 uprisings led by William Lyon Mackenzie in Upper Canada and Louis-Joseph Papineau in Lower Canada. While these rebellions were marked by violence, they remained relatively small in scale and ultimately proved futile. Nonetheless, they garnered enough attention to prompt Britain to dispatch Lord Durham to investigate the underlying causes.

Durham’s 1839 report recommended the cultural assimilation of the French into the predominantly English majority under a framework inspired by American-style liberty. However, the report faced widespread disapproval from both English and French populations, highlighting a fundamental historical contrast between the establishment of rights in Canada and the United States.

While the American founders drew upon early Enlightenment principles, seeking to swiftly transcend religious, ethnic, linguistic, and cultural differences, Canada’s official establishment, guided by figures like Robert Baldwin and Louis LaFontaine, adopted a gradual and pragmatic approach. They placed a premium on preserving cultural bonds and establishing traditional provinces where consensus between the French and English was pivotal in making sovereign decisions during the formation of democratic rights in Canada.

Black also traces the trajectory of Quebec’s “group” rights over the past 150 years in politics and the courts. On one hand, Quebec successfully preserved much of its cultural heritage within the English-speaking majority. On the other hand, Quebec’s leaders repeatedly and overtly encroached upon individual rights, often with increased frequency.

Within Quebec’s Civil Law tradition, judges exhibited a significant tolerance for legislation that curtailed individual liberties when it purported to safeguard Quebec’s minority status within the broader context of English-speaking Canada.

Illustrative instances include Quebec’s infamous 1937 Padlock law, permitting the provincial government to shutter meeting places of suspected communists, and the Roncarelli v. Duplessis case, where the Quebec government revoked the liquor license of a restaurateur who had posted bail for Jehovah’s Witnesses arrested for distributing religious pamphlets. In both cases, Quebec courts justified these actions as essential to protect Quebec’s culture, yet appeals to Canada’s English-majority Supreme Court resulted in these decisions being overturned. Such rulings often bolstered Quebec politicians and fueled Quebec nationalism.

Among recent challenges to English-speaking rights in Quebec, Bill 96 in 2023 imposed limits on the number of students in junior colleges who could study in English and mandated that companies with 25 to 49 employees adopt French as their official language. The most recent affront to rights occurred in October when the Quebec government announced that out-of-province students studying in Quebec would pay double the tuition of Quebecois residents, purportedly to mitigate the “anglicizing effect” they might have in Montreal.

Troublingly, these laws not only infringe on English-speaking rights and freedoms in Quebec but were enacted when the rest of Canada took significant measures to safeguard the rights of French individuals outside of Quebec and promote and prioritize French in Canada. This included initiatives such as bilingualism and fiscal programs that favoured Quebec.

Canada’s abolition of slavery

A myth that Forgotten History helps to dispel is the belief that Canadians should feel guilt and shame for the crime of slavery.

In fact, Canada’s record on abolishing slavery is something we can be legitimately proud of. At a time when slavery was practiced by almost every culture in all parts of the world, the British began to see it as indefensible on moral grounds, and so began implementing measures to abolish it starting in 1772 and abolishing it throughout the British Empire by 1833.

When Quebec was handed over to Britain in 1763, Black writes, there were fewer than 100 African or East Indian slaves in the territory, and by 1792 there were fewer than 300 slaves in all of Canada. Although slavery in Canada was officially abolished in 1833 alongside the rest of the British Empire, anti-slavery sentiments and its practical abolition were a fact of colonial life in Canada much earlier.

For example, in 1783, Lower Canada Lieutenant Governor Guy Carleton risked reigniting the Revolutionary War with the Americans by protecting and harbouring 3,000 fugitive slaves from George Washington. And in 1793, Lieutenant Governor John Simcoe made it illegal to bring slaves into Upper Canada. He also emancipated the children of all enslaved people.

In the 30 years leading up to the American Civil War, Canada became a refuge for about 40,000 fugitive slaves and was home to many notable anti-slavery campaigners such as Harriet Tubman, John Brown, and Josiah Henson. Furthermore, at least 11 black Canadian fugitive slaves or children of slaves became doctors in Canada and served in the Union Army during the American Civil War.

Finally, as many as 40,000 Canadians enlisted in the Civil War to fight against the Confederate States and bolster the anti-slavery cause. Considering what was practiced in other countries and cultures across the globe at this time, modern-day Canadians can be legitimately proud of most of Canada’s record in abolishing slavery.

Indigenous Peoples

Forgotten History also helps to dispel some common misconceptions about aboriginal history, most recently propagated by the “decolonization” movement.

Black points out that, prior to colonization, aboriginals lived in rigidly patriarchal nomadic tribes that were sparsely populated across the territory now called Canada. These tribes practiced slavery and corporal punishment and were engaged in routine inter-tribal warfare. This included the practice of torturing and executing the losing side in battle, including their women and children. The fact that some now consider Western civilization in Canada to be a criminal invasion or illegitimate occupation, Black remarks, is “an outrage … and a double blood libel on earlier generations of English and French Canadians.”

Much as the British viewed the abolition of slavery as a moral duty rooted in their Christian faith, Canadians applied similar moral principles when engaging with Indigenous peoples. As Black points out, although it requires a degree of cultural presumption for Europeans to believe that a government should undertake the task of reshaping an entire culture, the proponents of the residential school program did not approach this endeavour “with a uniformly negative attitude of racist superiority.” Instead, they were hoping to spare Indigenous children a life of grinding poverty, illiteracy and hopelessness by integrating them into the modern world.

Black also writes that the official 1857 residential school guidelines, “An Act to Encourage the Gradual Civilization of Indian Tribes in the Province and to Amend the Laws Relating to Indians,” the final aim was to remove all legal distinctions and create equality between Aboriginals and other Canadians. The guidelines did not denigrate the traditional aboriginal cultures, nor were Aboriginals officially encouraged to discard them.

To be sure, the children who were taken from their homes without sufficient explanation and the distressing number of instances where criminal abuse did occur is a serious stain on Canadian history. But, Black argues, it is a gross historical inaccuracy to conflate residential schooling with the charge of “cultural genocide,” as has former chief justice of the Supreme Court of Canada, Beverly McLachlin.

Ultimately, Black concludes that the civil rights record on Indigenous issues in Canada is weaker than in other areas such as democratic rights and rights of citizenship. In Black’s view, what is needed for the Aboriginal community is “a new framework for official native jurisdictions, the administration of government funding to assist the Aboriginal communities, and the establishment of appropriate rights for Aboriginal individuals to be more or less integrated into Canadian life, more or less established in a semi-separate aboriginal society, and to move between them as they might wish.”

Regardless of what one thinks of Black’s proffered policy recommendations, the romanticization of pre-colonial aboriginal society and the recent “overhasty and histrionic reactions” to news coverage have impeded Canada’s ability to reconcile its past.

In recent years, there has been a tendency to paint the past with one broad brush, and Forgotten History helps to restore nuance to these discussions so that informed judgements can be made. Although history cannot and should not guide every problem we face today, we should at least begin analyses by consulting it.

Robin Varma is the research director for the Aristotle Foundation for Public Policy. He holds a PhD in political science from Carleton University and is the author of Ruling Bodies: A Study of Coercion and Punishment in Plato’s Republic, Laws, and Gorgias (Lexington Books, 2022).

For interview requests, click here.

The opinions expressed by our columnists and contributors are theirs alone and do not inherently or expressly reflect the views of our publication.

© Troy Media

Troy Media is an editorial content provider to media outlets and its own hosted community news outlets across Canada.