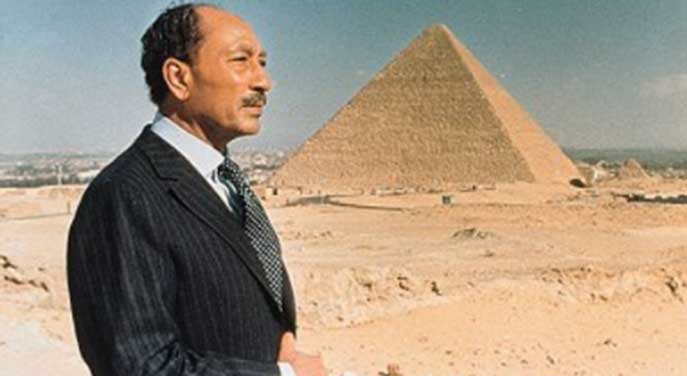

On Oct. 6, 1981, Egyptian President Anwar Sadat was gunned down while presiding over a ceremony celebrating the eighth anniversary of the Yom Kippur War. It was a brutal reminder of how passionate political differences can claim the lives of even the most prominent.

On Oct. 6, 1981, Egyptian President Anwar Sadat was gunned down while presiding over a ceremony celebrating the eighth anniversary of the Yom Kippur War. It was a brutal reminder of how passionate political differences can claim the lives of even the most prominent.

Political assassinations weren’t exactly unheard of in the second half of the 20th century. But this one had an additionally sinister element. It was an inside job, planned and executed by a dissident army faction pursuing Islamic revolution. In their eyes, Sadat had committed the cardinal sin of making peace with Israel.

Sadat came from a family of 13 children and was of mixed Egyptian and Sudanese ancestry. His father was a civil servant.

Sadat was a nationalist. In his younger days, he’d been dedicated to expunging British power and influence from Egypt. To quote historian David Reynolds, “his eclectic group of nationalist heroes included Gandhi and even Hitler. As an army officer in 1942 he was involved in an inept conspiracy to turn the Egyptian forces over to Rommel.”

When Sadat ascended to the Egyptian presidency following Gamal Abdel Nasser’s 1970 death, his overriding priority was to recover the territory lost to Israel in 1967. Hence the 1973 Yom Kippur War, which – while a failure militarily – was seen as restoring Egyptian pride.

When Sadat ascended to the Egyptian presidency following Gamal Abdel Nasser’s 1970 death, his overriding priority was to recover the territory lost to Israel in 1967. Hence the 1973 Yom Kippur War, which – while a failure militarily – was seen as restoring Egyptian pride.

Not long after, Sadat decided that enlisting the United States to lean on Israel was the smartest route to his objective. To that end, he threw in his lot with the new American president, Jimmy Carter.

Although personal relations only get you so far in international affairs, they do matter. And Carter and Sadat gelled big-time.

Speaking at the University of Maryland in 1998, Carter described Sadat as the greatest leader he’d ever met. Moments later, he talked about their April 1977 first meeting and the “strange rapport with that man that has been almost unequalled in my life.” Sadat’s visit introduced him to “a bright shining light.”

The feeling was apparently reciprocated, Sadat writing that “Jimmy Carter is my very best friend on earth.”

In the domain of hard-headed global politics, this was unusual. Perhaps even a little weird.

Good and all as the relationship was between, say, Ronald Reagan and Brian Mulroney, it’s difficult to imagine either of them expressing something quite like that about the other. And if they did, their respective constituents would’ve felt queasy.

Always susceptible to theatricality, Sadat made a dramatic move in November 1977. He would, he declared, “go to the ends of the earth” in his quest for peace. He’d even go to the Israeli parliament. He was in Tel Aviv 10 days later.

Then, anxious to capitalize on this movement and concerned that it was running out of steam, Carter invited Sadat and Menachem Begin, the Israeli prime minister, to a September 1978 summit at Camp David, the presidential retreat northwest of Washington. He would put his diplomatic skills to work with a view to bridging the differences between the two, thus bringing peace to the Middle East.

Carter subsequently described Begin as having “probably the highest intelligence of any man I have ever known.” But they didn’t get along.

Begin was a Polish Jew whose perspective revolved around two things:

- The lands Israel had taken in 1967 were part of the biblical heritage of Judaea and Samaria. They would never be surrendered.

- And having lost family members – including both parents and a brother – to the Holocaust, he would never allow Israel’s security to be dependent on unreliable others. Maintaining Israel’s strength and defences was paramount.

After 13 days of tense and tetchy negotiations, the process produced what’s known as the Camp David Accords, one of which led to the March 1979 Egypt-Israel Peace Treaty. For that, Sadat and Begin – but not Carter – nabbed a Nobel Peace Prize.

However, the reaction was very different in the Arab world. There, Sadat was denounced, Egypt was ostracized and its Arab League membership was suspended.

Carter later remarked on the gap between private and public statements. Saudi Arabia, he said, was privately supportive of the treaty. Still, it joined the other Arab leaders in public condemnation. Fear is indeed a terrible thing.

And Sadat paid for it with his life, surviving for less than two hours after the attack of Oct. 6, 1981. The assassin, Lt. Khalid al-Islambouli, was executed the following April.

Troy Media columnist Pat Murphy casts a history buff’s eye at the goings-on in our world. Never cynical – well, perhaps a little bit. For interview requests, click here.

The views, opinions and positions expressed by columnists and contributors are the authors’ alone. They do not inherently or expressly reflect the views, opinions and/or positions of our publication.

© Troy Media

Troy Media is an editorial content provider to media outlets and its own hosted community news outlets across Canada.