This month’s holiday celebration, much like the year in general, is one that the annals of history will always remember. For my last column of 2020, let’s explore some historical analysis that few would ever recall.

This month’s holiday celebration, much like the year in general, is one that the annals of history will always remember. For my last column of 2020, let’s explore some historical analysis that few would ever recall.

Who won the American Civil War?

The correct response would be: the North, Union, Union Army and/or Army of the Potomac.

While history may show the South – or the Confederate states, Confederate Army and/or Army of Northern Virginia – lost on the blood-soaked battlefields, it may have won the war of ideas and influence more than 150 years after the last shot was fired.

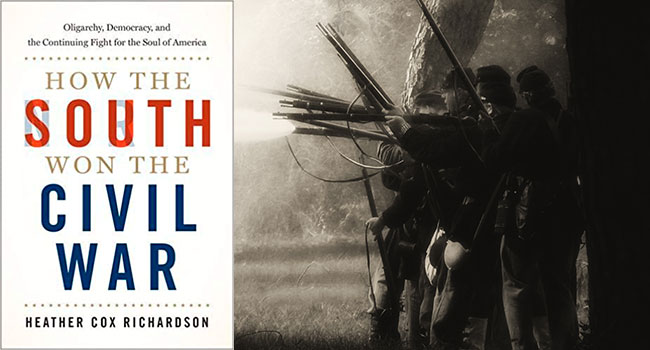

That’s the premise of Boston College history professor Heather Cox Richardson’s controversial book How the South Won the Civil War.

While the Confederacy failed to supplant the rights, freedoms and equality of all people, she believes the “Confederate ideology took on a new life … and came to dominate America” in the West. Hence, “the American paradox has once again enabled oligarchs to threaten democracy. They have gained power by deploying the corollary to that paradox: equality for all will end liberty.”

This time, it’s the American West, not the Old South, leading the charge.

The Confederate States led by Jefferson Davis utilized various race-oriented, market-oriented theories to justify entering the Civil War. It was a brutal struggle that divided families, friends and neighbours. The Union ultimately won and President Abraham Lincoln triumphantly called it “a new birth of freedom.”

Richardson believed this was an illusion.

While Republicans were “erasing racial categories from American law,” and working toward women’s rights and human equality, post-war settlers were heading West. Indeed, the western cowboy was celebrated by departing southern Democrats as a “hardy individualist, carving his way in the world on his own,” and they were viewed collectively as “brave heroes who worked their way to prosperity as they fought for freedom and American civilization against barbaric Indians, Chinese, and Mexicans.”

The author then took a stunning leap of faith to meld the views and values of the West with the Old South. “By the end of the nineteenth century,” Richardson suggested, “western leaders had internalized the idea that democracy was, in fact, a perversion of government – exactly as southern leaders had done in the immediate postwar years. They argued that small farmers, cattlemen, and miners were not promoting American prosperity and voting legitimately for policies that answered their needs. Instead, they were illegitimately skewing government in their own interests and against what their employers were sure was best for the nation.”

She argued this is “what southern Democrats had said about African Americans during Reconstruction. In that era, race had become class; now class had become race.” This led to the shift in historical narrative from Democrats to Republicans supporting the Confederacy of the West.

The rest of Richardson’s story is predictable.

She claimed Republicans used language and rhetoric that “sounded remarkably like that of slaveholders.” Barry Goldwater’s 1964 presidential campaign “personified the post-Civil War western cowboy” and gave birth to conservatism movement.

Ronald Reagan’s 1980 victory brought “the South and the West together to take over national politics” and “destroyed the activist state” to the point where wealth moved upward, and women and minorities “headed toward positions of subordination.”

The trend continued with Newt Gingrich’s Republican Revolution, the Bush family and Donald Trump.

In Richardson’s view, “America was on its way to becoming an oligarchy.”

She couldn’t be more wrong.

Briefly, her interpretation of movement conservatism is wildly inaccurate. It was an intellectual awakening focused on creating small government, lower taxes, and more individual rights and freedoms. That’s what specifically motivated Goldwater, Reagan and many other Republicans.

This supposed link to racialized politics and policies from the Old Confederacy may fascinate liberals and “progressives”, but it’s unreal and unworthy of further discussion.

As for the American West, it’s obviously had moments of imperfection in helping form this perfect union. Drawing a historical line from Western individualism and liberty to Confederate defiance and intolerance, as Richardson did, takes nerve and a fruitful imagination. The South lost the American Civil War in 1865, but the ghost of the South has never led a Civil War revival in the American West.

History is in the eye of the beholder. Even if that eye has several thick layers of dirt and grime that need to be removed immediately.

Happy New Year, everyone – and all the best for 2021!

Michael Taube, a Troy Media syndicated columnist and Washington Times contributor, was a speechwriter for former prime minister Stephen Harper. He holds a master’s degree in comparative politics from the London School of Economics.

For interview requests, click here. You must be a Troy Media Marketplace media subscriber to access our Sourcebook.

The views, opinions and positions expressed by columnists and contributors are the author’s alone. They do not inherently or expressly reflect the views, opinions and/or positions of our publication.