During its 113-year history, only 15 of the thousands of Indian residential school workers were ever found guilty

By Hymie Rubenstein

and Rodney Clifton

Allegations of widespread abuse against the children who attended Canada’s Indian Residential Schools (IRSs) began their slow but steady promotion three decades ago.

Since that time, Indigenous activists increasingly began pushing more scurrilous assertions about the IRSs, especially those administered by the Roman Catholic Church, with a sharp uprise starting on May 27, 2021.

On that day, the Tk’emlúps te Secwépemc Indigenous band of Kamloops, British Columbia, issued a press statement claiming the discovery of the “remains of 215 children who were students” of the Roman Catholic-run school.

Hymie Rubenstein |

Clifton Rodney |

The Kamloops announcement, still not confirmed, became Canada’s George Floyd moment: flags on government buildings were lowered for nearly six months, statues of Canadian heroes were defaced, destroyed, or removed, and dozens of mainly Catholic churches were vandalized and burnt on and off Indigenous reserves.

New burial finds prompted cries of proof of a previously hidden “Holocaust” or “Final Solution” of Indigenous people. The Kamloops school was alleged to have been a “concentration camp,” with the supposedly revealed burials evidence of a horrific crime.

The Catholic Church, which managed 43 percent of IRSs, has responded to the recrimination, including the charge of genocide, with several apologies, including papal ones in 1984, 2009, and 2022, as well as dozens more at the diocesan level.

But how true are these accusations?

A 1996 report by the Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples showed students complaining mainly about hunger, poor food, and physical abuse. Importantly, most of the sexual abuse was confined to predation by fellow students.

More recent research has shown that of the thousands of IRS workers living in the schools during its 113-year history, only 15 were found guilty of sexual abuse, including a lone Catholic priest.

Compared to intra-Indigenous sexual abuse on and off Aboriginal reserves, this figure is very low.

As for the genocide accusation, a large and growing body of evidence shows no confirmed evidence of even a single child murdered at any IRS.

Nor do any of the complaints about the boarding schools ever mention that similar negative experiences, including harsh corporal punishment such as caning and strapping, were widespread in boarding and other schools for non-Indigenous students during the same period.

Though serious IRS condemnations are largely unconfirmed, including the charge that students were forced to attend boarding schools against the wishes of their parents, proof of compassionate IRS treatment by priests is as conclusive as it is comprehensive.

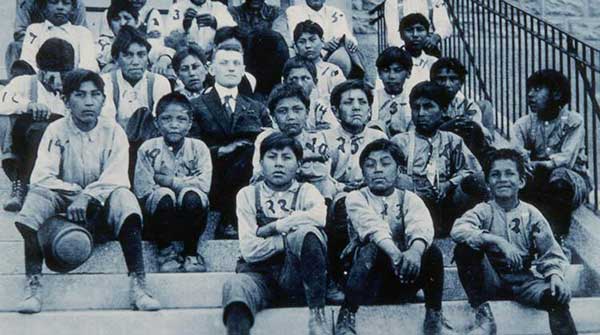

Carefully preserved records, such as those available on the Indian Residential School Records site, document the loving care given to thousands of Aboriginal children, composed mainly of orphaned, abused, and neglected youngsters, to enable them to adapt to life more easily in a rapidly changing Canadian society.

So far, the Roman Catholic apologies have not resulted in reconciliation with Canada’s Indigenous peoples. In fact, reconciliation may be impossible because the allegations against the churches have been directed at extracting compensation from both the churches and the federal government.

Even so, decades after most schools were closed, the problems said to be caused by them have remained, if not expanded. Nationally, Indigenous children under 14 account for about 54 percent of children in care, according to the 2021 census, despite Indigenous children being fewer than eight percent of Canada’s youthful population. In Manitoba, 91 percent of children under the care of family services agencies are Indigenous.

Reasonable people might wonder how the Roman Catholic Church’s involvement in running IRSs can continue to be blamed for ongoing tragedies like this, especially when most of their victims have no experience or family history of residential school involvement. What the historical record does show is a Church that did much to deliver a better way of life to many Indigenous children.

Unfortunately, this same Church can no longer defend itself, fearing that this would label it as composed of callous and unrepentant Indian Residential School denialists.

Rodney A. Clifton is an emeritus professor at the University of Manitoba and a senior fellow at the Frontier Centre for Public Policy. Hymie Rubenstein, editor of REAL Indigenous Report, is a retired professor of anthropology and was a board member of and taught for many years at St. Paul’s College, University of Manitoba, the only Roman Catholic higher education institution in Manitoba. Both are authors of Residential School Recrimination, Repentance, and Reality for the Frontier Centre for Public Policy.

For interview requests, click here.

The opinions expressed by our columnists and contributors are theirs alone and do not inherently or expressly reflect the views of our publication.

© Troy Media

Troy Media is an editorial content provider to media outlets and its own hosted community news outlets across Canada.